Issues related to the TMJ (temporo-mandibular joints) can affect patients of all ages, and the first step to finding solutions and deciding treatment is to develop an accurate diagnosis. Similar to how an orthopedic surgeon would evaluate a problem with a patient’s shoulder, knee, or hip, establishing a diagnosis for the TMJ involves acquiring detailed information via MRI or CBCT technology. Below is an article written by Dr. Lemieux and published in the Fall journal of the Dental Society of Greater Orlando in 2019. If you have concerns about your jaw joints, have unresolved pain, or have noticed changes in your bite and want to learn more, please give our office a call.

“As dentists, it is clear that we have a calling to be more than “tooth fixers”. Beyond the repair and replacement of teeth, our responsibilities include understanding and managing occlusion, screening for oral cancer, critiquing and planning for cosmetics concerns, recognizing and assessing airway problems, and understanding the impact of systemic health issues.

One area that is often overlooked, mismanaged, or ignored are issues stemming from breakdown within the temporomandibular joint complex. One study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services suggests that over 10 million Americans suffer from some form of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). As TMD can significantly affect a patient’s oral health, it is imperative that we are able to recognize and establish a proper diagnosis of the type of TMD in order to appropriately manage these patients.

TMD encompasses a variety of potential problems a patient may have. While many TMD patients have issues stemming from muscle spasm secondary to bruxism or clenching, some have issues within the joint itself. Signs of internal derangement can include unresolved pain, sudden changes in bite, restrictions in movement, and deviations in path of motion. Often times, there are clues within the occlusion that can suggest the presence of joint breakdown like an anterior open bite of more than 2mm, an overjet of more than 2mm, a midline shift, etc. Muscle spasm and splinting can often be managed by a properly made occlusal appliance, but issues within the joint itself require further assessment.

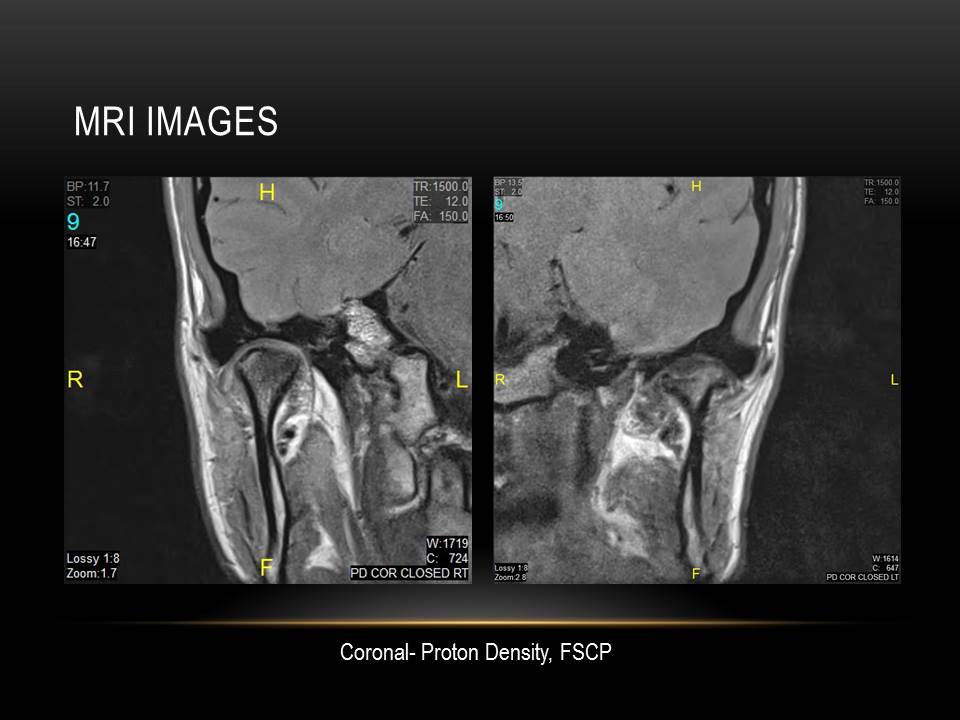

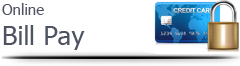

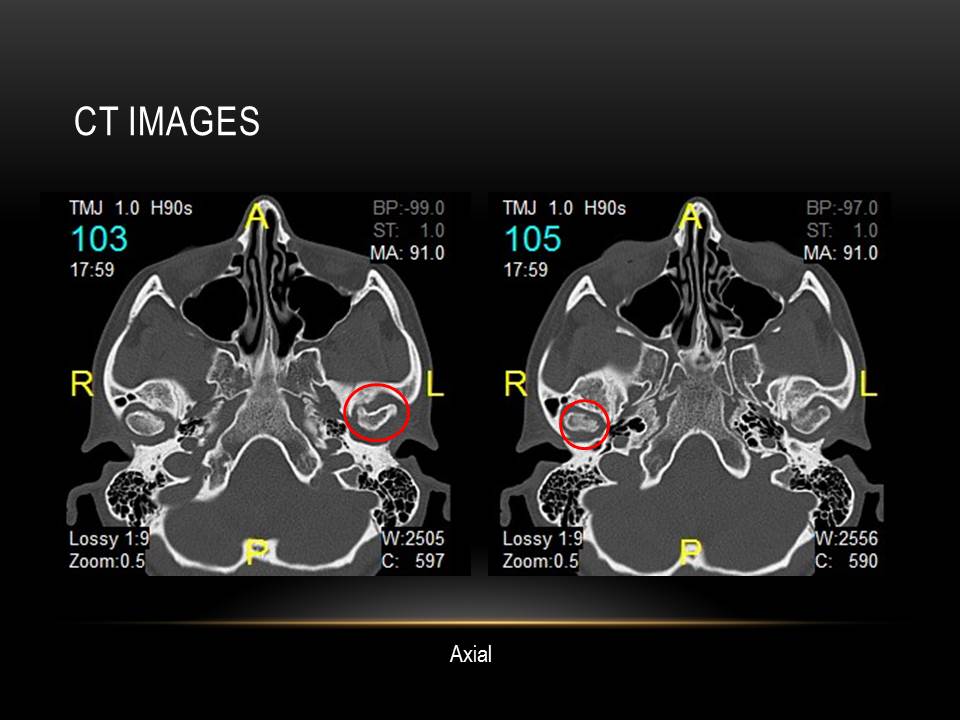

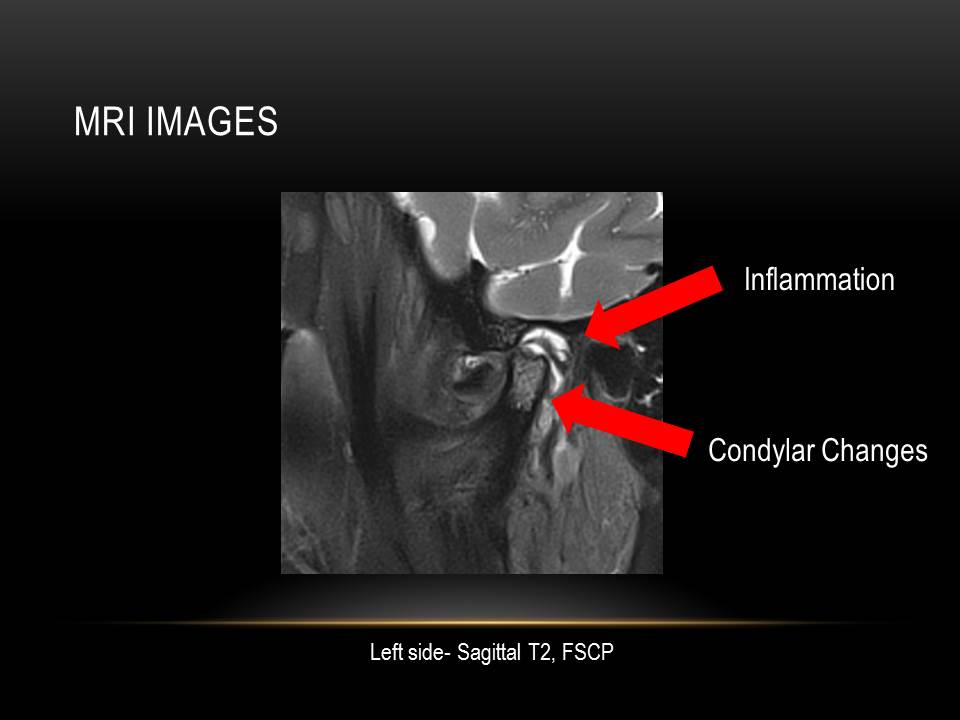

Indirect assessment of a joint includes joint palpation, muscle palpation, joint loading, listening for clicks, pops, or crepitus, Doppler auscultation, and studying the way a patient opens and closes their jaw; however, direct assessment of the joint requires the use of imaging. Due to the three-dimensional shape and orientation of the joints, a simple panoramic radiograph is insufficient. A CBCT or CT is necessary to assess hard tissues within the joint, examine condylar size and shape, evaluate for boney breakdown of the condyle and fossa, study ramus size, and more. With a CBCT or CT, one can infer where the disc is by looking at the joint space between condyle and fossa, yet the disc cannot be visualized. An MRI is necessary to directly assess the soft tissue and can give insight into the size, shape, location, and condition of the disc, and screen for joint inflammation or effusion. Whereas as CBCT or CT is taken at one position, typically where the joints are fully seated, MRI images are taken at several bite positions to assess where and how the disc behaves as a patient opens and closes.

Requesting joint imaging takes some planning and is not as simple as sending a patient to an imaging center with an unspecified prescription. First, it’s helpful to find an imaging center utilizing either a 3-Tesla MRI magnet or a 1.5-Tesla magnet with TMJ coils. The resolution on a 1.5-Tesla magnet alone can be difficult to see diagnostic information about the disc. The imaging center will want to know what your differential diagnosis is, and will need details about which joint positions you are wanting for the MRI. Lastly, while the radiologist will provide a diagnostic report, it’s important to personally review the images to establish your own diagnosis for the joints. The more images you see, the better you’ll get at recognizing structures and problems.

Until you begin looking for it, it’s hard to imagine how many of your own patients possess some degree of TMD issue. Many of these patients have joint pain and have tried conservative methods which have not been successful, but few have actually been imaged. When conservative methods are failing, and other signs and symptoms of internal derangement are noticed, it’s critical to establish a diagnosis first. As we won’t begin endodontic therapy on a tooth without a radiograph, we should view joint imaging along these same lines. Remember, too, that imaging does not necessarily mean a patient needs joint surgery. Imaging allows a patient to make an informed decision about their joint condition and provides useful information to the clinician about appropriate, and often times, conservative options.

Imaging has allowed me to identify degenerative joint breakdown on a 73 year old patient who struggled to yawn without pain, to assist a 24 year old post-orthognathic surgery patient who continued to have bite changes with unresolved pain, to diagnose an anterior disc displacement on a 13 year old patient who developed an anterior open bite despite not having a tongue thrust, and numerous others. These patients are looking to us for guidance and understanding.

I encourage you all to include in your differential diagnosis of bite changes and joint pain considerations for TMD, and I encourage you to learn more about the benefits of imaging. There are resources in our state who can provide education and training to improve this important skill set, and increase your understanding of TMD. Your patients are certainly counting on you to help them!”